THE best place in Kabul for military booty was always the Bush Bazaar.

Most of the goods for sale had fallen off US lorries — so cheeky tradesmen named the market after the former president who invaded Afghanistan in 2001.

But when I visited the market yesterday there was a clear sign how Kabul has changed.

The president’s name had been painted over.

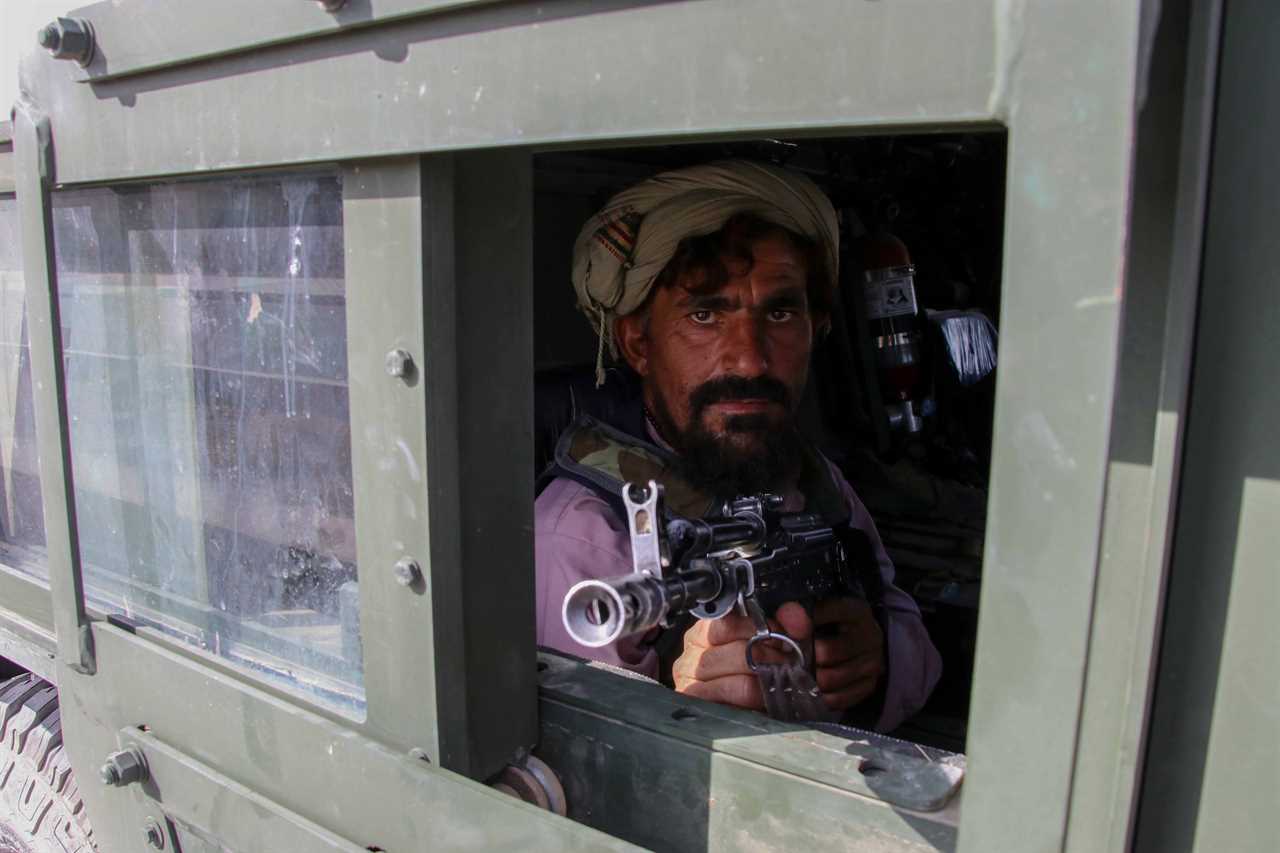

And the other shoppers were Taliban.

Three of the Islamic militants asked how much it would cost to fit their Kalashnikovs with mounts for laser sights and torches.

They asked about US-style body armour.

In the slang of the British army they wanted to look “ally” — and they were very friendly about it.

Despite the horrific reports of revenge killings and beatings meted out elsewhere in the country the soldiers I have met around Kabul have been polite and reasonable.

They are more surprised to see me than I am to see them.

Read our Afghanistan live blog for the latest updates

The problem for me at the Bush Bazaar was the shopkeepers were scared of the Taliban.

The US gave Afghanistan 16,000 pairs of night vision goggles along with half a million guns, most of which were captured in the Taliban’s lightning advance last month.

But instead of flooding the black market, the supply has dried up.

A shopkeeper told me: “Soldiers used to bring things here.

“Sometimes people who worked on the bases, like cleaners and cooks, would bring things here.

“But now the bases are closed, the soldiers have all gone, and the Taliban have taken over. They are very strict and people are scared of them.”

Even before the Taliban came, night vision goggles were highly sought after — and almost always stolen — so they were kept under the counter.

The dealers told me to come back in a few hours, so together with an Afghan colleague we set off for the old British embassy to search for the missing portraits of the Queen.

Diplomats fled in chaos last month and Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab claimed Her Majesty’s portraits had been destroyed before they retreated to Kabul Airport.

One of those portraits used to hang in the embassy lobby where receptionists sat behind bulletproof glass and visitors traded their passports for visitors’ passes.

FEARING FOR THEIR LIVES

The Queen was wearing a pale dress with a blue sash and a tiara. Next to her was Prince Philip.

The drive across town took about 20 minutes — which was faster then I remembered.

The traffic in Kabul is terrible but there are hardly any checkpoints now because there is no point looking for Taliban.

They are everywhere.

Part of the journey took me on foot along the banks of the Kabul river, where suddenly I heard a commotion and a Taliban pick-up roared past with at least on prisoner on the back.

He was surrounded by Talibs and wailing as one of the militants whipped him with what looked like a thin strip of birch.

A shopkeeper saw the shock on my face and laughed.

“A thief!” he said enthusiastically. “It is good the Taliban caught him.”

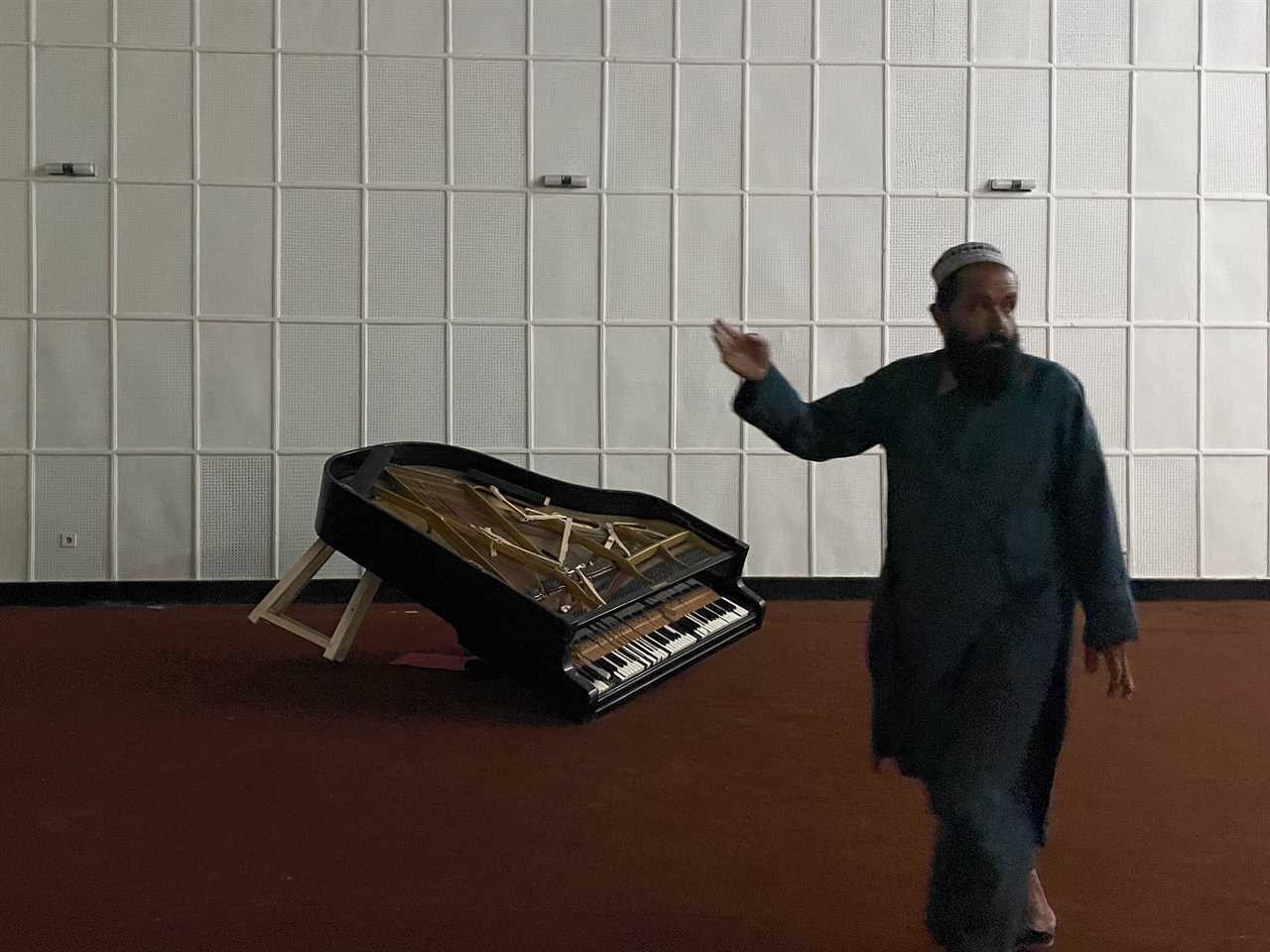

Along the way we see two grand pianos at a government-run recording studio which were probably destroyed by the Taliban — who think music is against Islam.

Arriving at the embassy gate — a concrete blast wall and lookout tower with rolls of razor wire — the first thing that struck me was that one of the Taliban guards had a navy baseball cap with the words “British Embassy Guard Force”.

Most of the men who wore those caps were left behind last month when our troops flew out without them.

They had been on a bus to Kabul airport but the Taliban turned them back

Now they are fearing for their lives.

To get in this time I didn’t need my passport.

I had my Taliban Press Pass — a letter-headed notepaper from Islamic Emirate, which was what the Taliban call Afghanistan, saying I am free to do my work.

The guard commander waved us past all the old security points

At the entrance to the chancery there were clear signs people left in a hurry.

A suitcase burst open with clothes on the street, an overturned trolley in the middle of the road and split cardboard boxes full of sleeping bags and blankets.

A few yards away, on the pavement, a flag was snagged on the thorns of a rosebush.

It belonged to the Royal Anglian regiment.

The Taliban were adamant the chancery was out of bounds.

The doors were locked so we snooped round the residences instead.

Papers which should have been burnt were strewn behind a house with details of Afghan staff and of people who had applied for jobs.

SHOT DEAD MUM-OF-FIVE

Defence Secretary Ben Wallace said Boris Johnson “will be asking questions” about the blunder, adding: “Clearly it’s not good enough.”

In a gaudy villa of the British Council a safe door had been ripped off its hinges.

My Taliban guides clamped the scarves to their noses when they opened a fridge with rotting food.

Inside was a also a drinks collection: Martini, Drambuie, Pernod and Angostura Bitters for the diplomats’ pink gin and tonics.

Sadly, no sign of Her Majesty’s portrait.

The protocol, the Foreign Office said, is for all images of the Queen to be removed in a diplomatic bag or destroyed on site.

Outside the gate I met a civil servant who hadn’t been paid for months.

He had resorted, in desperation, to selling Taliban flags to try and make ends meet.

With time to kill before we head back to the market, we stopped at the national football stadium where the Taliban held a public execution in 1999, shooting dead a mum of five in front of a packed crowd.

Bilal Ahmad Hamza, 33, the Taliban commander in charge of the ground, assures me it would not be used for executions in future.

“We have other places for that,” he says.

As we walk around the grounds one of Bilal’s entourage comes up and says: “I used to live in Chelsea and I worked in Shepherd’s Bush.”

“Are you Taliban?” I asked.

“Yes,” he laughs. And then he shows me a picture of himself in a phone repair kiosk in London.

We have a late lunch of kebabs at a famous Afghan restaurant near a city park and then head back to the Bush Bazaar.

One of the stall holders has sourced not one, but two sets of night vision goggles.

They work. They are amazing. This was cutting-edge tech in 2006 when British troops first went to Helmand.

Night vision gave Nato forces an edge.

Now everyone can buy it off the shelf.

Almost everyone, that is.

The seller wants $1,700 dollars that I don’t have.

The banks aren’t working in Kabul so cash is in short supply.

And while we’ve driving, I have been googling night vision goggles.

They cost about the same price new from dealers in the US.

It is a relief, in a way. Some things haven’t changed.

The mobile internet is surprisingly good — and the city is still expensive.