HE chose England.

So it is an irony befitting Shakespeare that the funeral of the Greek-born prince, who became the Duke of Edinburgh and the Queen’s strength and stay, should decide the fate of his grandson; the young man who so publicly abjured the country beloved to his heart, along with its mores and its heritage.

Read our Prince Philip funeral live blog for the latest updates

For it will be beside the coffin of Prince Philip that the Duke of Sussex, who returns to these islands as a foreigner, will take or reject the hand of reconciliation.

Of all those in Harry’s family, it was Philip perhaps who found his departure from The Firm and the nation the most baffling and incomprehensible.

During the last year of the Duke’s life, he would refer to the Sussexes’ departure with bewilderment. Indeed, according to those who knew him, the high-profile circus act of Megxit hurt him like the bite of a tiger.

These days, the word “honour” does not mean much. When one hears of the alleged honour of politicians or do-gooding celebrities, one naturally guffaws. But Prince Philip was a man of honour to his core.

We all know the Duke liked to swear a good deal, was sometimes rude and insensitive and had a keen eye for a pretty ankle.

No amount of varnishing could make him fit for adulation in the halls of political correctness, a position that Philip, thank God, would abhor with liberal use of the F-word.

But honour is a different kettle of royal fish, and his philosophy of life was to make the best of what had been dealt him.

It was notable that Philip, whose youth had been very difficult indeed, never felt sorry for himself.

Even so, his self-control was sorely tested by his grandson and The World’s Greatest Victim. Poor Philip. This was a man who had so carefully turned himself, for want of a better phrase, into the first gentleman of the land.

His agony over Harry was the agony of someone of intensely patriotic and civilised feelings thrown into a situation of intolerable vulgarity, destructive alike to the peace and dignity of the family of which he was head in all but name.

He said: ‘I didn’t like the Germans much’

His whole nature cried out against it; exasperated. For Harry had consciously rejected and reviled the very values by which he had charted his life.

Born Philippos of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg, Prince of Greece and Denmark, the only son of Prince Andrew of Greece, the future Duke of Edinburgh was evacuated from his country hidden in a fruit box after the family were exiled by a revolutionary court.

A penniless prince without a throne, with a mentally ill mother and a father who relinquished his parental duties, his childhood was even more unstable than Harry’s.

There was nothing inevitable about Philip’s migration to the country that would take him to its heart.

He was sent to school in Paris, then briefly England, before attending the Schloss Salem School in Germany, a country where his sisters had married German aristocrats. This was in the 1930s, during the rise of Hitler.

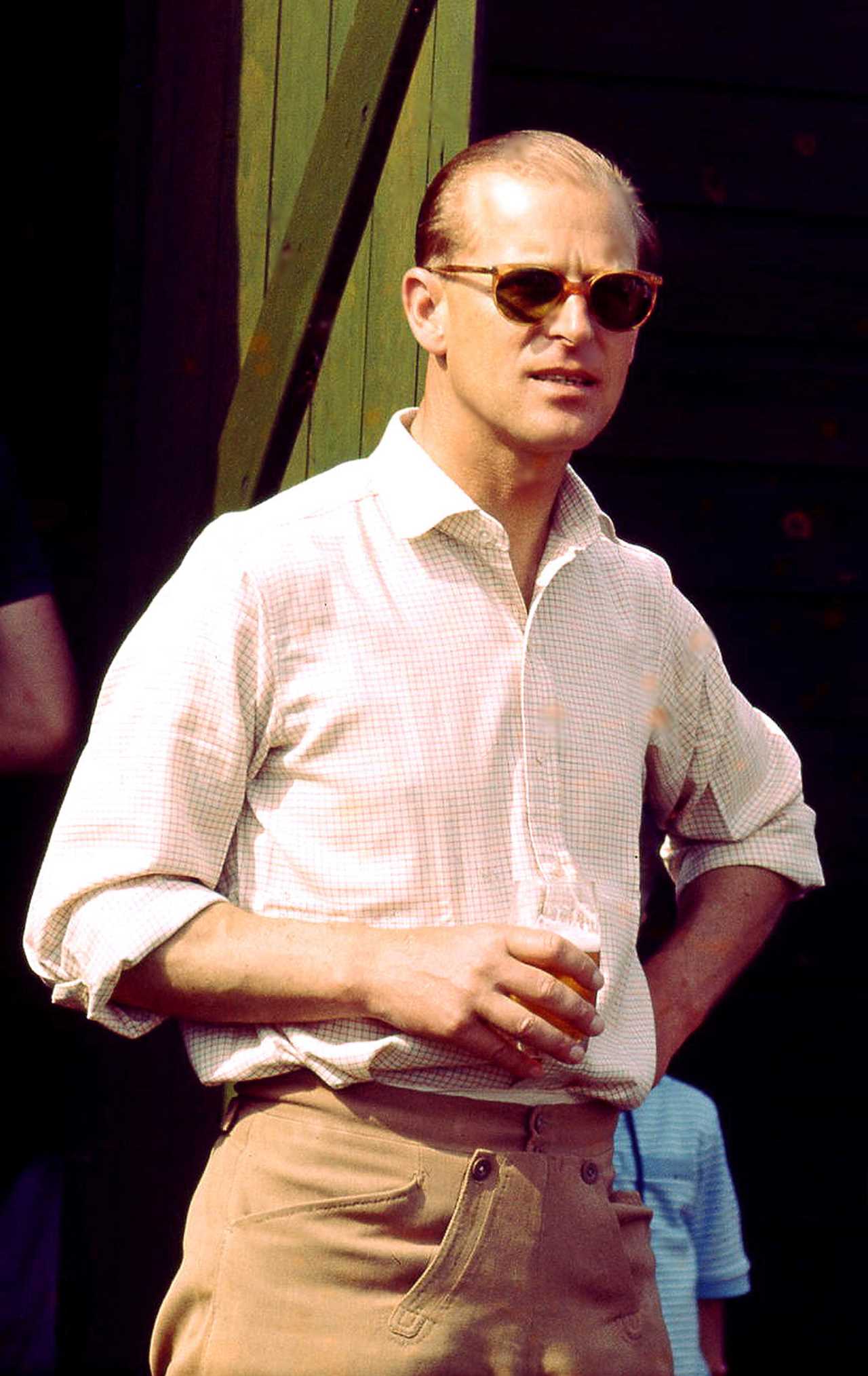

Philip might have stayed there. Already handsome, he was also a member of a European royal house, albeit an impoverished one. A life of luxury without responsibility in German high society would have seemed to many an ingratiating proposition.

But during one of the occasions when I met Prince Philip, at Royal Ascot — and yes, his eyes did twinkle in my direction — he remarked, “I didn’t like the Germans much”.

It was in England that he saw the essentials of a decent society, a clean tradition, public spirit, honesty and courage.

His maternal relatives had prospered in the Royal Navy, including uncles “Dickie” Mountbatten and brother Georgie, from whom Philip acquired his love of gadgets and machinery.

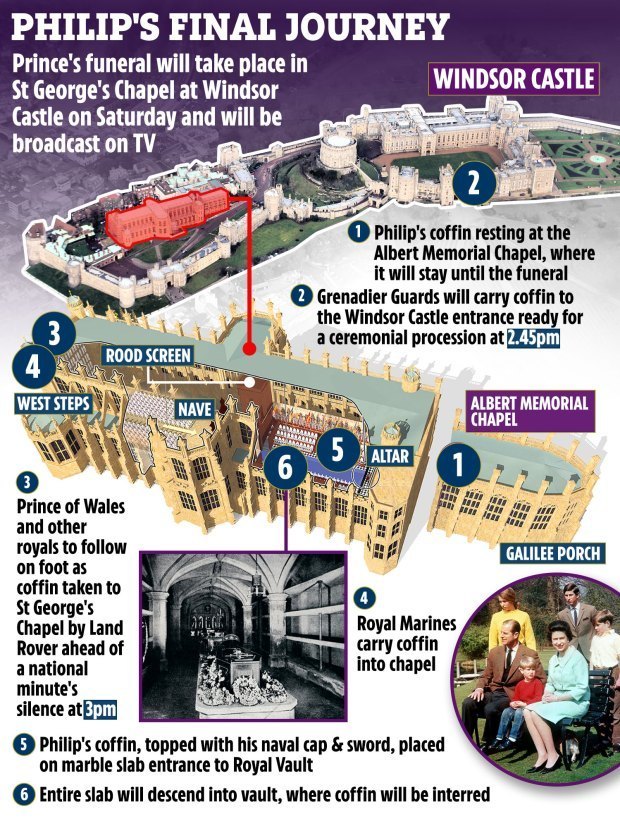

Georgie had the unsung distinction of designing his own Teasmade 20 years before it became commercially available, and taught the young Philip how to convert the inside of motor vehicles, thus unknowingly contributing to the Duke’s idiosyncratic decision to be conveyed to St George’s Chapel on a Land Rover for his funeral.

So Philip chose England. He decided to attend the new Gordonstoun School, founded in 1934 by the Jewish-German Kurt Hahn, an outspoken critic of the Nazis. Philip was 12, and by all accounts fiercely independent.

As he grew up he almost consciously rejected everything Greek or Danish, determined to make himself into the beau ideal of an Englishman.

Hanh later said: “No doubt for a short time he was tempted by the comfort likely to come to a Prince of Greece resident in Europe but he was nevertheless determined to join the Royal Navy, as ‘England is my home’.”

The society heiress Gina Wernher, whose family had him to stay at their country seat, Luton Hoo, and who became a close friend, once observed: “Philip could have married into any European royal family. There were quite a few princesses, including Danish ones, who saw him as a tremendous catch.”

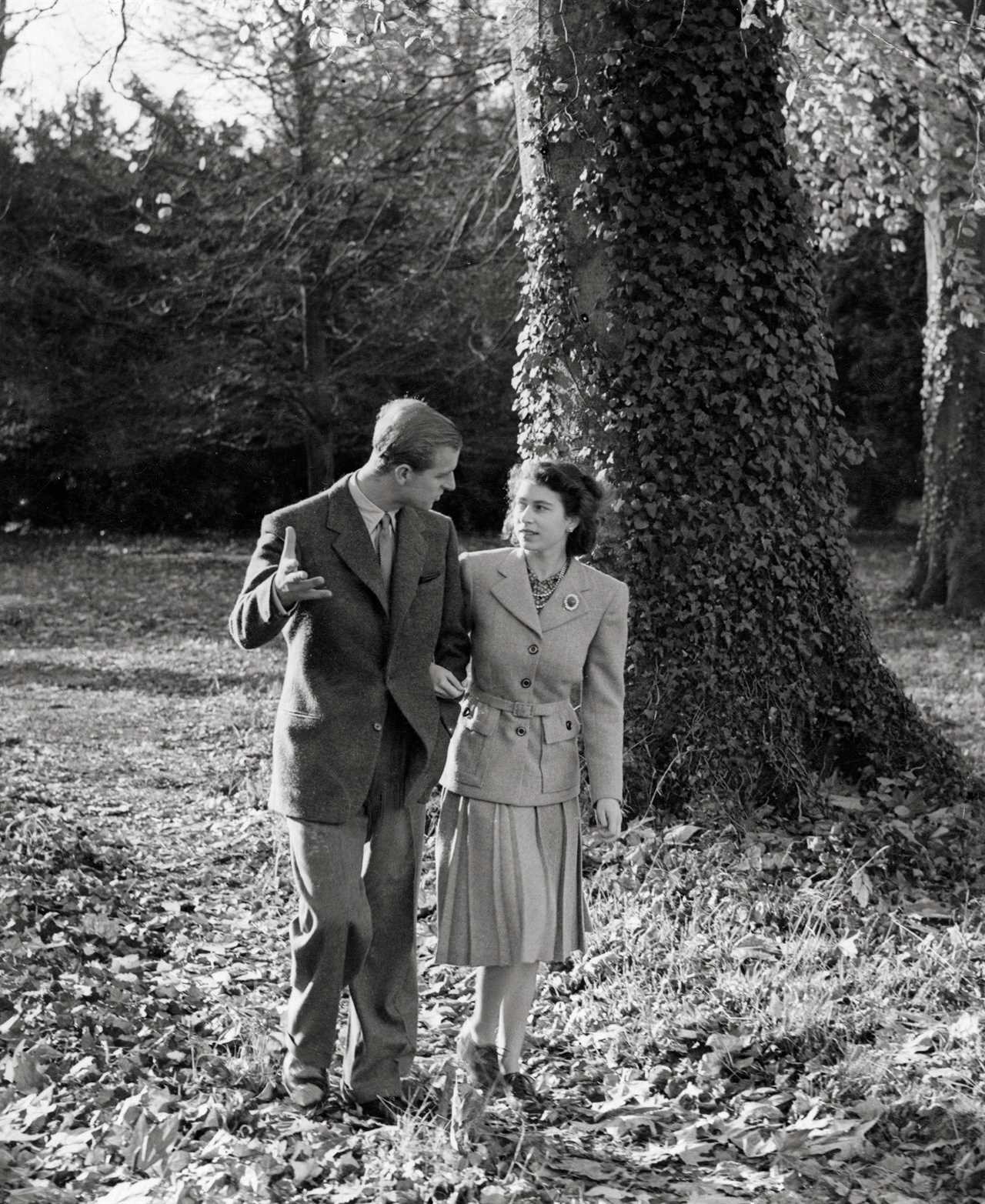

But the rest is history. He fell in love with the young Princess Elizabeth and changed his name to Philip Mountbatten.

In 1952, she became Queen. Earl Jowitt, then Lord Chancellor, prophesied at the time: “We must be thankful that she has by her side her Consort, the Duke of Edinburgh, who has so completely identified himself with the people of this country and their way of life.”

The Duke was defined by patriotism. He was a dark horse made suddenly formidable by the hand of fortune and his innate understanding of the fact that the monarchy existed due only to public consent.

It was Philip who pulled its socks up, often to the howls of fustian courtiers, who preferred the institution to be as arcane as it had been in the Middle Ages.

From the televising of the Queen’s Coronation, to inviting the BBC to film the royals en repose, Philip devoted himself to the task of protecting The Firm, which he steered through waters that were sometimes very choppy indeed.

Neutral, aloof and seasoned, he developed inner integrity. But in the last year of his life, it was Harry who shook him.

His much-loved grandson had repudiated England, and in doing so rejected everything Philip held dear, and, worse for this austere, unshowy man, he had rejected it for the hollow gaudiness of Hollywood and the celebrity circuit.

One might say that much of the British nation has repudiated many of Philip’s values, particularly those of public service and quiet stoicism.

But it must have been bitter fruit indeed to have his grandson, to whom he had been so close, do the same. For Harry and Philip were very close.

Life gave them commonality; the loss of a parent, a love of the military, of conservation and the clean life of the outdoors.

Harry’s existence in LA would have seemed one of grotesque futility, of money grubbing and backroom bartering, of becoming a sort of tawdry, bargain-basement prince.

But fate stepped in, and the Duke of Sussex has a golden chance to make a gesture of contrition; to remember who he is and where he came from and what he has thrown away.

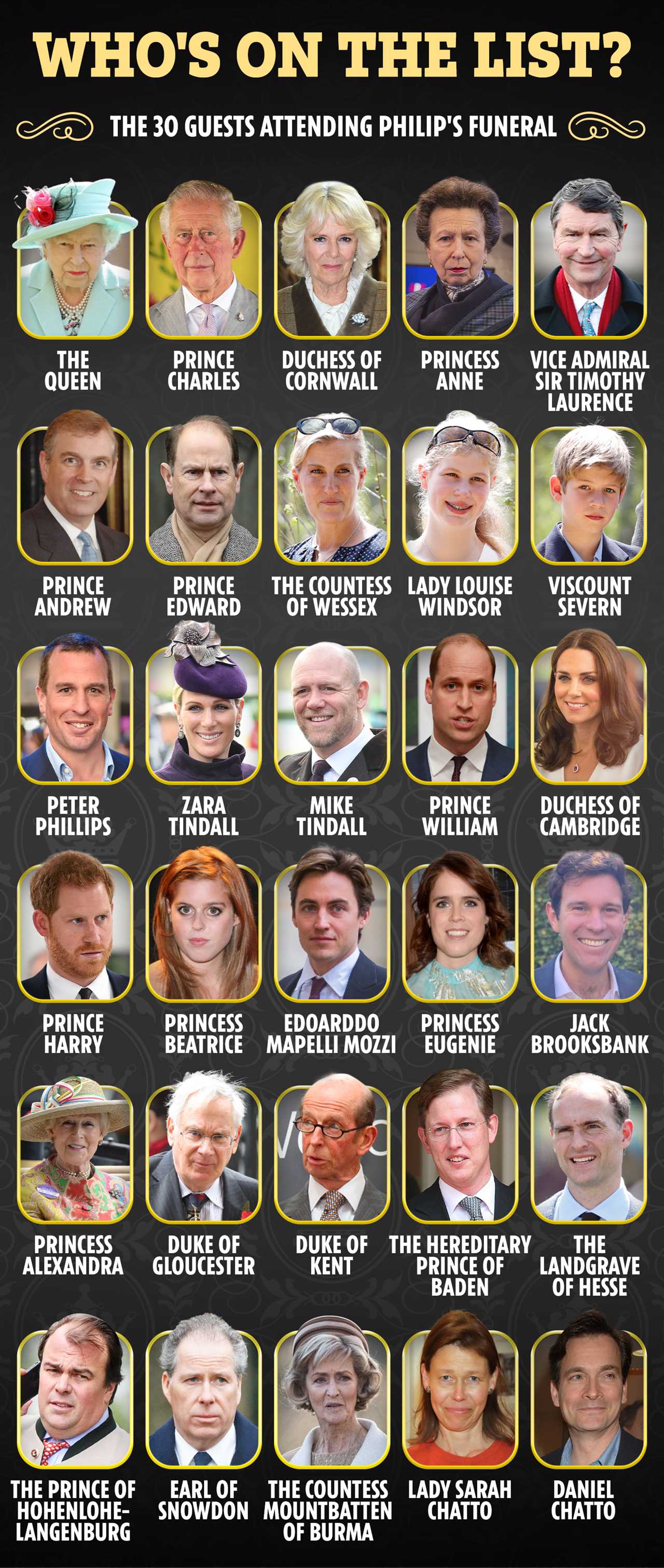

Philip’s funeral, as befits the private man, will be small and there will be plenty of opportunities for dignified and emollient words. Sadly, there is also potential for a further rift. Let Harry think a little on his selfishness, the hurt he caused a Grand Old Man and how even cynics have recognised the passing of a Titan.

I incline to believe that the inscrutable gods, carrying Prince Philip off when they did, were very kind to him. Had he lived, he would have become increasingly unhappy and confused by his helplessness.

Resting at last at Windsor, he will mingle for ever with the soil of England that he found so blessed.

The real tragedy, indeed, is not Philip’s death at the ripe age of 99, but the passing from the public life of this country of the spirit he so deliberately chose to embody, which needed no title to gild it, no state funeral to recognise its incalculable worth.

Above all, the Duke loved the young and strove to pass the torch to a new generation. On the occasion of his passing, it would be a fitting tribute if both his grandsons took up the flame.

It is not too late for Harry to choose England, too.

Did you miss our previous article...

https://thecelebreport.com/royalty/who-is-donatus-landgrave-of-hesse