SHE arrived in the middle of a national crisis.

When Princess Elizabeth Alexandra Mary of York was born at 2.40am on April 21, 1926, in the calm of a Mayfair townhouse, Britain was days away from the General Strike.

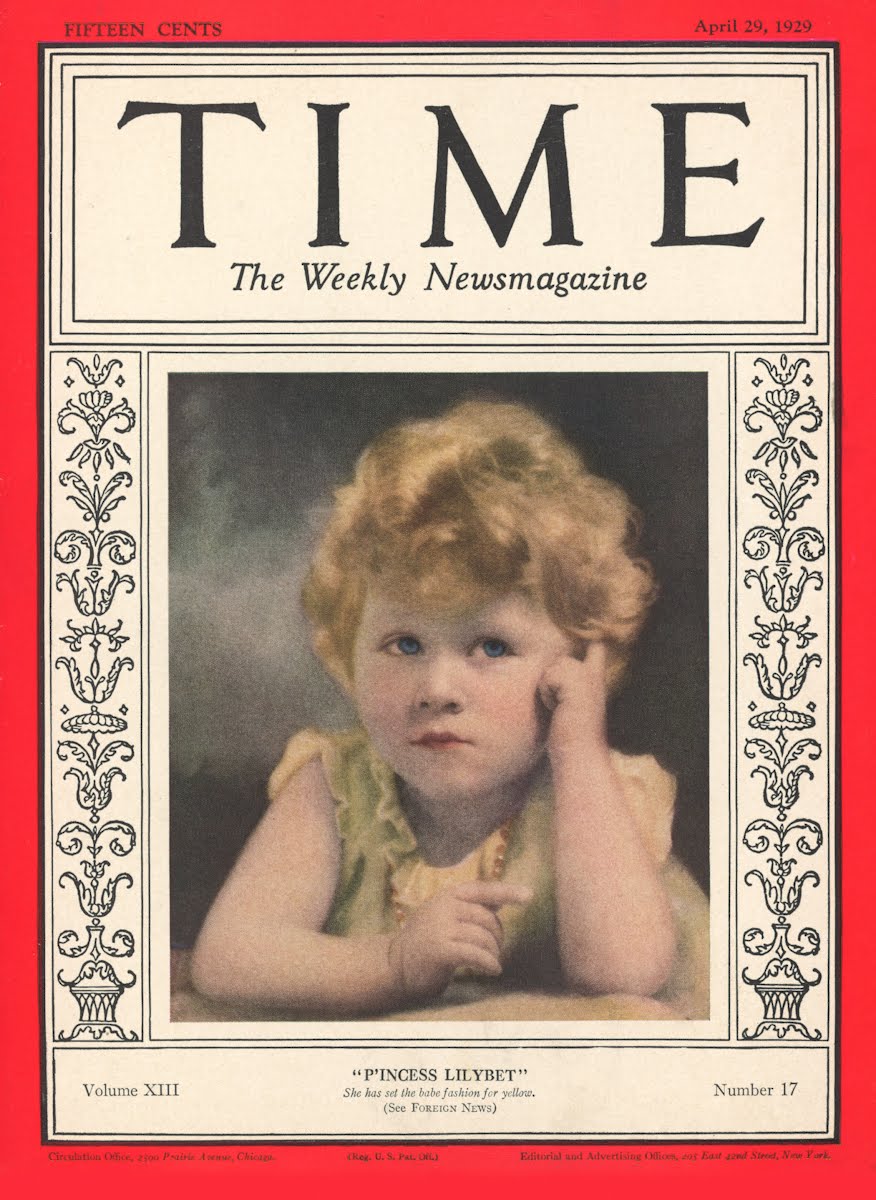

‘Princess Lilybet’ making the news on the front of Time magazine in 1929

Now we are six… the Princess in 1934

Tangled talks to avert the TUC shutdown were failing. Some feared it would start a socialist revolution that would sweep the old order away — just as had happened with baby Elizabeth’s royal relations in Russia nine years earlier.

Under an absurd tradition from 1688 — when James II’s Queen Mary was accused of sneaking in a male baby in a warming pan to ensure a Catholic heir — the Home Secretary had to witness all royal births.

So Sir William Joynson-Hicks had to tear himself away from strike talks with coal bosses to hang around in the drawing room at 17 Burton Street and await the arrival.

Reporters camped outside the townhouse in weather so appalling that father-to-be the Duke of York sent out coffee and sandwiches.

FAREWELL MA'AM

Latest Queen Elizabeth tributes as Britain begins period of mourning

In a difficult labour, his 25-year-old wife gave birth by Caesarean, or in the phrase of the time, “a certain course of treatment”.

The parents were overjoyed. The Duchess of York, Scottish society beauty Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, had always wanted a girl. Her husband, 30-year-old Prince Bertie, the socially introverted second royal son with a debilitating stammer, declared his “happiness complete”.

Elizabeth’s birth was noted across the Empire, with the Viceroy of India ordering bells to be rung.

King George visited with Queen Mary, who reported: “Such a relief and joy . . . a little darling with lovely complexion and pretty fair hair.”

The little darling was never expected to be Queen. She was third in line to the throne, after her uncle the Prince of Wales and her father — and she was expected to slip further down in time.

The Prince of Wales was only 31. He would surely marry and produce his own heirs. Elizabeth’s mother, only 25, would be likely to have sons, who would go ahead of her newborn in the royal line.

Such was the princess’s unimportance that she was allowed to be born at a private house, the London home of her mother’s parents. All previous monarchs had been born in castles or palaces.

A small crowd of well-wishers had formed on the day of her birth and stayed for weeks. But to escape the larger General Strike throngs, Elizabeth’s pram was smuggled out by the back door.

The strike lasted just nine days, with 1.7million stopping work. The upper and middle classes had volunteered as “key workers”.

Princess ‘Lilibet’

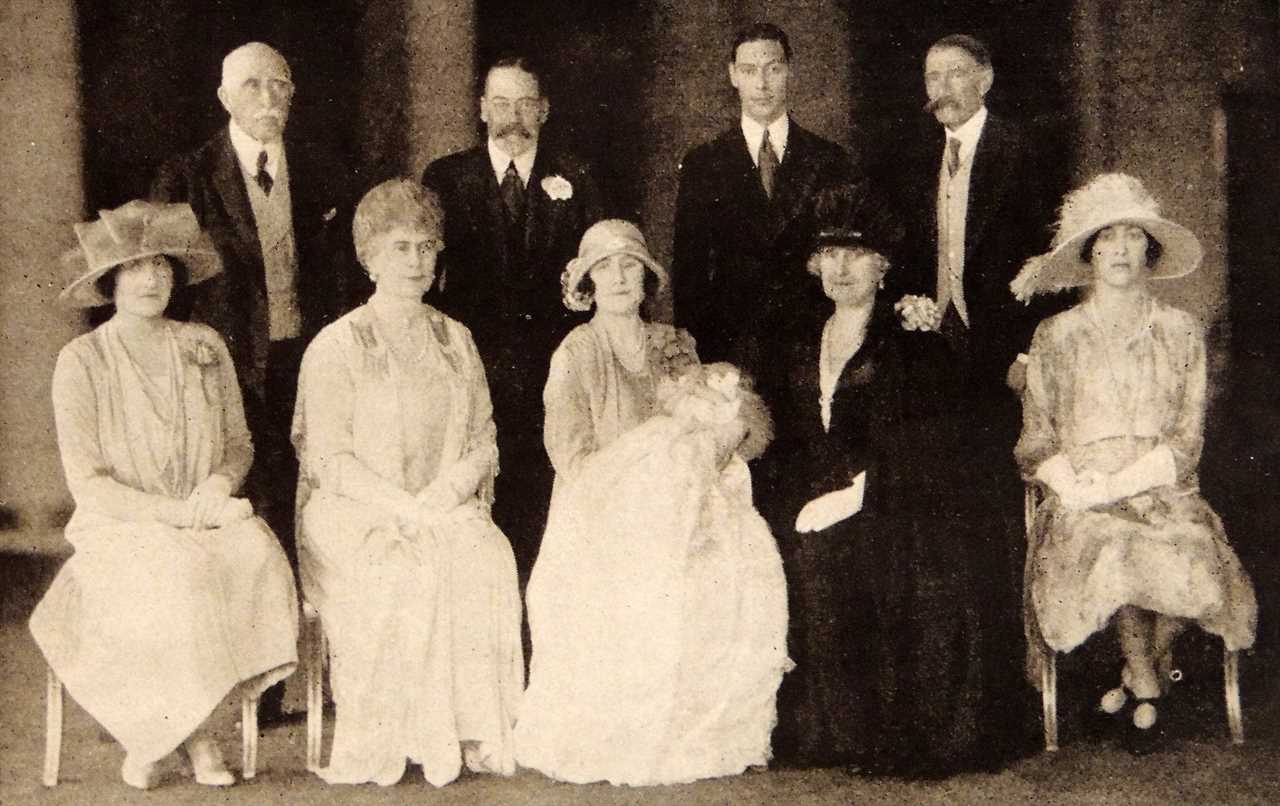

On May 29, Elizabeth was christened with water from the River Jordan in the Private Chapel at Buckingham Palace before six godparents: Grandfathers George V and Claude, grandmother Queen Mary, two aunts and one great-uncle, 76-year-old Prince Arthur, Queen Victoria’s last surviving son.

The baby, just over a month old, wore a lace gown that great-great-grandmother Victoria had used at the christening of her first child, Princess Victoria, in 1841.

For her first few years Elizabeth was looked after by the formidable Clara Knight, an ultra-strict yet kindly nanny who had brought up her mother. Clara, entirely unmodern, controlled Elizabeth’s every moment.

She was regaled with stories of “when mummy was a little girl” and allowed only one toy at a time.

Small York… Duke and Duchess, Bertie and Elizabeth, with their baby

The princess called Clara “Alla”, a nickname that stuck. Elizabeth found her own name a mouthful too — calling herself Tillabet, Lisabet and Lilliebeth before eventually arriving at Lilibet, the name her family called her for life.

She spent her first summer at Glamis Castle in Forfarshire, home of her grandparents — the first of many childhood trips to Scotland.

In January 1927, with Elizabeth nine months old, her parents left on a six-month tour of Australia and New Zealand. It was an ordeal for Bertie, whose boyhood shyness had developed into a stammer which made him a hopeless public speaker.

The gruelling tour, including a speech opening the Australian parliament in the new capital of Canberra, was his first big test in royal life and deemed a success.

Hailed by crowds, the couple were bombarded with good wishes — and three tons of toys for “Baby Betty”.

At a welcome home reception in Buckingham Palace, the Duchess grabbed Elizabeth from her nurse, hugging and kissing her and saying, “Oh, you little darling!”

The following year, with the princess 14 months old, her parents acquired their first home of their own.

Life at One-Four-Five

In June 1927 the family moved into 145 Piccadilly, a five-storey pile down the road from the palace. It had 26 bedrooms, a ballroom, an electric lift and a garden with a gate that led to Hyde Park.

And while the Duke of York was determined it would be a relaxed and intimate family home, he still insisted on a red carpet in the nursery.

One-Four-Five, as the family called it, was destroyed by a German bomb in 1940. But for a few years it was the centre of what Elizabeth recalled as an idyllic childhood, surrounded by love and laughter — and doting, tactile, attention from her parents that was unusual in families of their social sphere.

Christening… from left: aunt Lady Elphinstone, Prince Arthur, Queen Mary, King George, Duchess and Duke of York, Countess and Earl Strathmore, aunt Princess Mary

The princess’s nursery was at the top of the house, amid the servants’ quarters, and her great joy was to play with her thirty 12in toy horses, whose saddles and harnesses she would polish before bed.

Every morning Elizabeth would run into her parents’ bedroom for what they called “high jinks”.

She popped in to see her mother and father every morning right up to the day she was married in 1947. She was also close to her grandfather, who she called “Grandpa England”.

The austere and intimidating King softened whenever she was around.

He would interrupt meetings to play with her, giving her a ride on his back in her favourite game of pony, or get down on all fours to be led around by his beard in “horse and groom”.

In 1928 when King George was dangerously ill with blood poisoning, visits from Elizabeth were “prescribed” to cheer him up.

Uncle David — Prince of Wales and the future Edward VIII — was perhaps Elizabeth’s most constant visitor, joining games of Snap and Happy Families. He also gave her AA Milne’s books Winnie-the-Pooh and When We Were Very Young, as well as her very first dog, a Cairn terrier.

Beyond this innocent existence, lived without any security and open for every passer-by to see, Elizabeth was the most famous little girl in the world.

By the time she was three she had appeared on the cover of Time magazine. Newspapers were beginning the feeding frenzy that would last for her whole life.

A Hollywood studio asked if they could sign her to a movie contract. When they were refused, they created their own little “princess” in Shirley Temple.

Sister act

When Elizabeth was four, her sister Margaret Rose was born. The princess called her Bud “as she is not a full-grown rose yet”.

King George forbade school, saying the only thing Elizabeth had to learn was good hand-writing. But the Duke and Duchess were determined their children should have as normal an upbringing as possible. Lilibet played with neighbours’ children, including Sonia Graham-Hodgson.

The Princess as a baby in 1926

Sonia later recalled: “She was thoughtful and sensitive. She never seemed aware of her position and paid no attention to people who stood by the railings to watch her.”

Queen Mary was delighted with Elizabeth’s upbringing.

“She leads such a simple life,” she said. “And is always punished when she’s naughty.”

With Alla looking after Margaret, a new influence came into the princess’s life — under-nurse Margaret MacDonald, a gardener’s daughter from Inverness-shire who would serve Elizabeth for 67 years.

“Bobo,” as she was known, became the Queen’s dresser and her trusted confidante, able to tell her things about herself others could not.

When Elizabeth was five, a new companion arrived — governess Marion Crawford, a 22-year-old teacher from Dunfermline.

The girls’ relationship with “Crawfie” was to end in betrayal and sadness when the governess published a “discreet and loving memoir”, but for the rest of their childhood years she was a light in their lives.

TEDDY TRIBUTE

Paddington Bear says ‘Thank you Ma’am’ in touching tribute to the Queen

The princess was just nine when her beloved George V died on January 20, 1936, aged 70. When she broke down in tears, Queen Mary explained that royals do not display sadness or happiness in public. It was a lesson she never forgot.

With Edward VIII King, she was now second in line. And though not old enough to fully appreciate the implications, she knew the world had shifted enough to ask her governess: “Oh, Crawfie, ought we to play?”