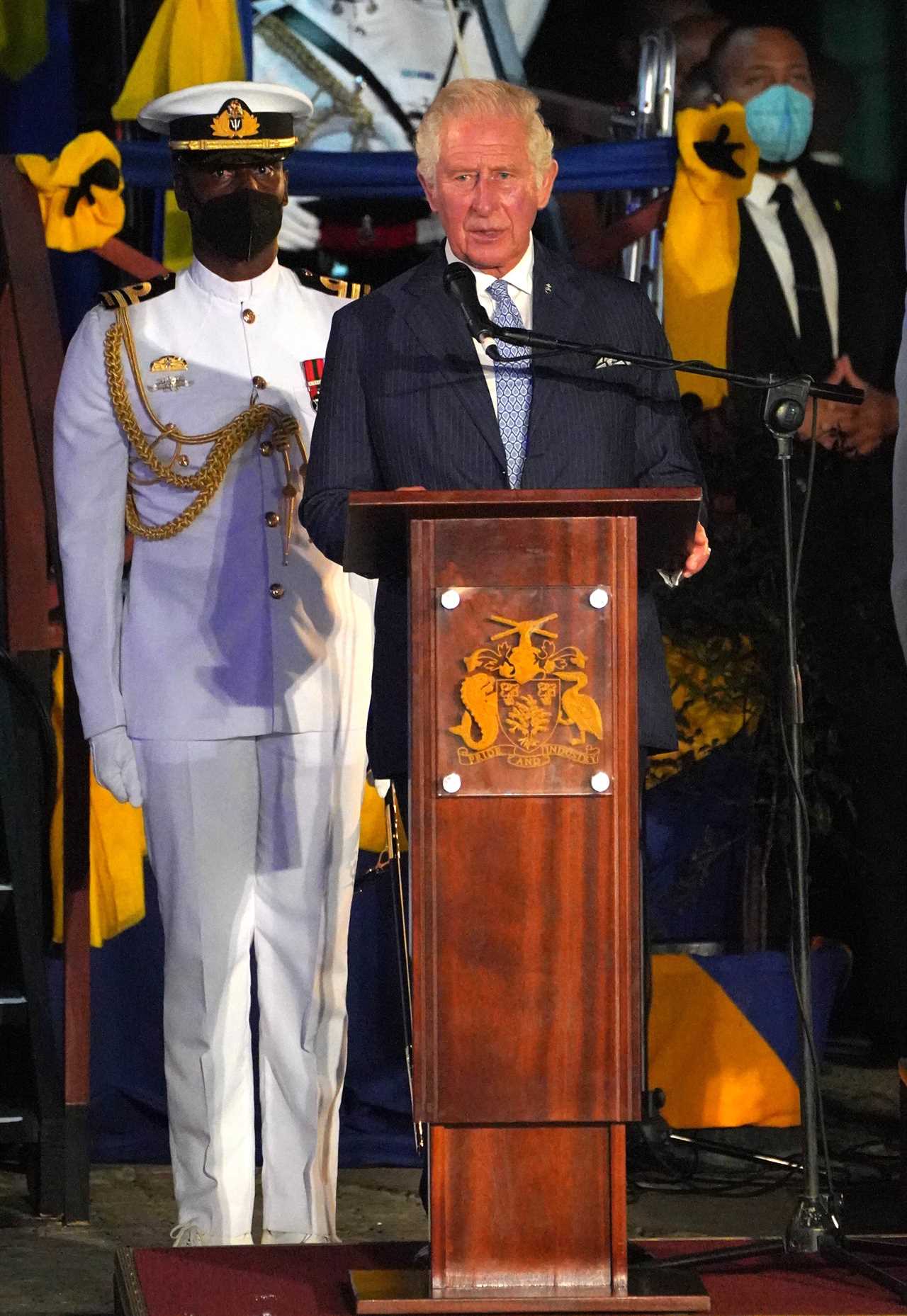

BARBADOS cut ties with the British monarchy today as it became a republic, marking the end of the Queen’s reign on the former island colony.

Her Majesty sent her “warmest good wishes” to the nation for its “happiness, peace and prosperity in future”, while Prince Charles made a landmark speech acknowledging Britain’s colonial past.

Outgoing Governor General and new President of Barbados, Dame Sandra Mason, said: “The time has come to fully leave our colonial past behind.”

The Queen insists ending her reign in any realm is a matter for the government and people.

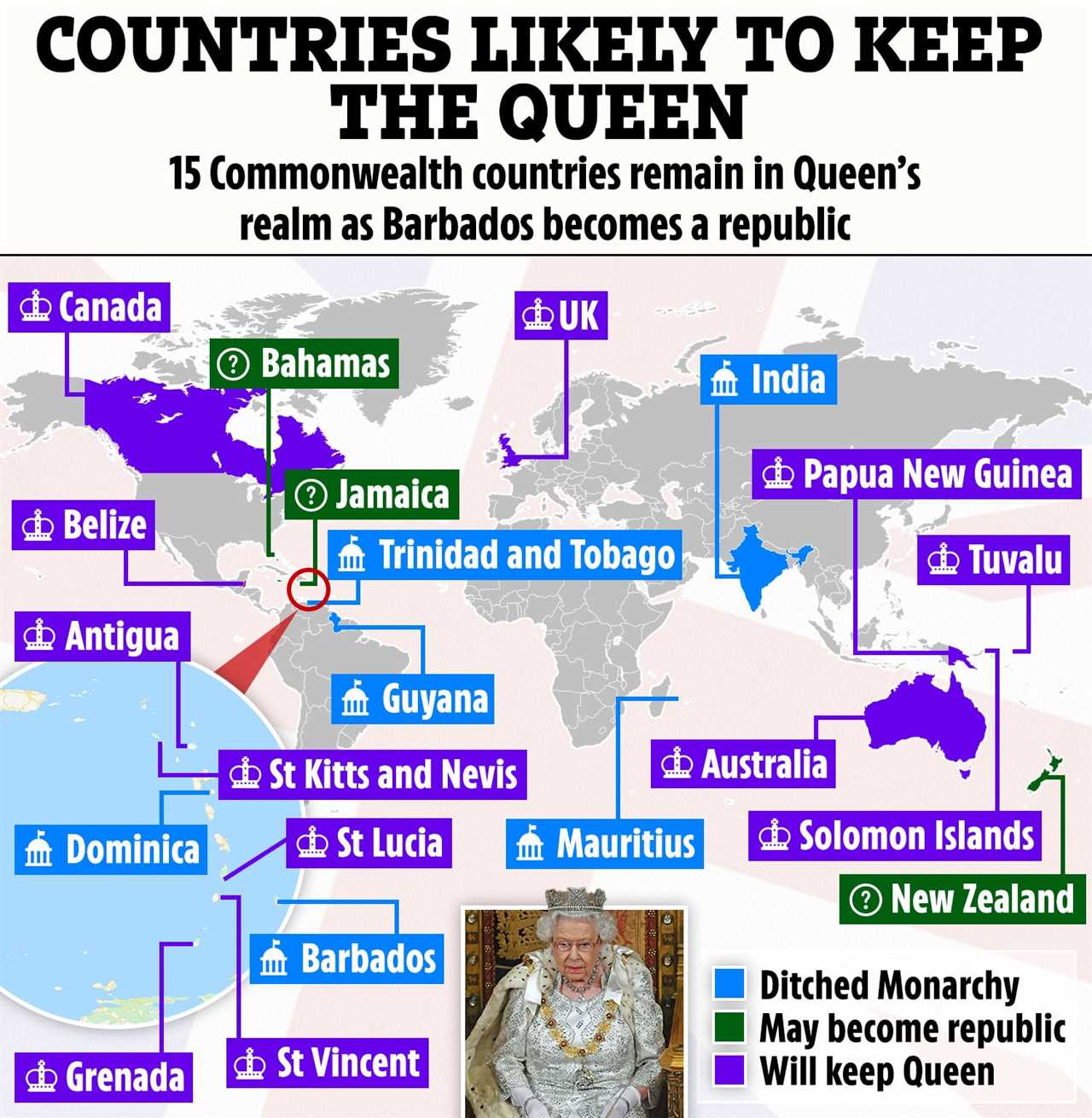

It is rare for a country to remove the Queen as its head of state. The last to do so was Mauritius in 1992.

Guyana took the step in 1970, less than four years after gaining independence from Britain. Trinidad and Tobago followed suit in 1976, and Dominica in 1978.

But with the Queen now 95, which of the remaining 15 Commonwealth nations are likely to follow the lead of Barbados and dump the monarchy?

Here are the odds on Commonwealth nations become republics.

Jamaica (2-1 on)

Leading politicians in Jamaica have long advocated the island nation becoming a republic.

Next year will mark 60 years of what anti-monarchists call “neo-colonialism” because the Queen remains head of state.

Labour Prime Minister Andrew Holness made dumping the monarchy a priority in his 2016 manifesto but has yet to call a long-awaited referendum.

Since gaining power he has focused on building a strong economy.

Now Jamaica’s Opposition Leader, numerous equalities campaigners and organisations are calling for the Queen to be removed as the nation’s head of state as the government prepares to lobby the UK for slavery reparations.

Mark Golding, who took over leadership of the People’s National Party (PNP) in November 2020, says it is of vital importance.

The difficulty lies in the Jamaican constitution, which has very high thresholds for any form of constitutional change.

But with Barbados finding a way, Jamaica is expected to be the next realm to fall as it explores ways of relaxing the strict rules.

Australia (1-2 against)

Australia has a love/hate relationship with the monarchy, but in recent years calls to dump the British royals have cooled.

“The best things in life are those that have stood the test of time,” Australia’s then PM Minister Tony Abbott said after the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge’s visit with baby Prince George in 2014.

The TV networks and commentators couldn’t get enough of the young prince – even the republicans were impressed.

One, Shelly Horton, said on Australia’s top breakfast show Sunrise: “I think he’s a republican slayer. He’s just so cute and William and Kate are such a lovely couple.”

She hit the mood of the country on the button, as “Prince of Cuteness” George seemed to put the case for ditching the monarchy in Australia back years.

The republican movement in Australia, however, has been strong for years.

They pushed for a referendum on the issue and the last country wide vote took place in 1999, but the republicans suffered a surprise defeat – 45 per cent to 55 per cent.

The co-founder of the Australian Republican Movement, Malcolm Turnbull, who was Prime Minister from 2015 to 2018, revived the idea with a wave of republicanism sweeping the nation.

In 2016, he said the issue would be raised again after the Queen’s death.

Since then, with the rise in popularity of the Cambridges and successful royal tours Down Under, calls for a republic have been dampened down.

An online Ipsos poll in January found 40 per cent of Australians were opposed.

New Zealand (2-1 on)

Another nation reportedly eager to become a republic is New Zealand.

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has previously declared she is in favour of cutting ties with the monarchy and having a national as Head of State.

Back in 2017 she told the Times newspaper: “I am a republican. It’s certainly not about my view of the monarchy but my view of New Zealand’s place in the world and carving out our own future. So that is what drives my sentiment.”

Becoming a republic will not affect New Zealand’s Commonwealth membership, or any realm wishing to ditch the monarchy, because Commonwealth member states have agreed that membership will continue when a state changes its constitutional arrangements.

After the 2020 General Election an online poll found that 20 per cent agreed that “New Zealand should become a republic”, with 36 per cent of the respondents remaining neutral and 44 per cent disagreeing outright.

The poll also found that 19 per cent wanted to change the national flag, and ten per cent wanted to change the country’s name.

Canada (1-5 against)

Canada is the oldest, most populated and most pre-eminent of the Commonwealth realms.

Arguably as American as it is British, it’s an amalgamation of three cultures, with French spoken as the first language by nearly a quarter of the population.

But recently Canadians’ love of the monarchy seems to be more tepid.

A new poll found the desire among Canadians to drop the monarchy is at its highest level for 12 years.

The poll, conducted by Research Co., found that 45 per cent of Canadians surveyed said they would prefer to have an elected head of state instead of the Queen, when considering Canada’s constitution.

It doesn’t appear to face any immediate extinction, even under Charles, and is likely to soldier on – mainly because it helps distinguish Canada from the US.

Antigua and Barbuda (1-5 against)

Granted independence from the UK in November 1981, Antigua and its tiny sister island Barbuda, are in no rush to become a republic.

Senior politicians say there is no appetite for that currently, believing they should focus on rebuilding the economy and establishing a programme of public education.

Barbuda, a private oasis of pink and white sand beaches, was one of Princess Diana’s favourite holiday destinations.

The Bahamas (even split)

The only realm to have had an ousted King, the Duke of Windsor, as its Governor General, its shift to a republic seems inevitable.

But change is more likely to be driven by politicians than the people.

There was no vast public appetite for The Bahamas to follow Barbados despite two previous Constitutional Commissions both recommending ditching the Queen.

That said there is an unspoken acceptance of the fact that in the evolution of the political society of The Bahamas, republican status is probably something that is inevitable.

Whether it happens in the next decade or the next 20 depends on what priority the government of the day will attach to it.

It would not require much change from the political landscape, just switching the role of Governor-General to President.

Belize (1-2 against)

Belize, which became a British colony in 1840, known as British Honduras, and a Crown colony in 1862, became independent from the UK in 1981.

Belize has a diverse society that is composed of many cultures and languages.

In July 2021 Prime Minister John Briceño strongly hinted the time had come for a discussion on the nature of the Belizean state, suggesting it become a republic.

He said: “Probably one of the things we will be talking about in the near future: whether we want to stay with the parliamentary system; or do we want to go to a republican system; or find a hybrid between a parliamentary system and a republican system?”

The Belize Progressive Party (BPP) has spoken openly about a “Republic of Belize” without the monarch as head of state.

There has been no public position from the United Democratic Party (UDP) or the Belize People’s Front (BPF), the other major parties.

But it is likely to be a long way off.

Grenada (1-2 against)

Grenada became independent on February 7, 1974.

But attempts by governments to ditch the Queen and other reforms have been rejected in two referendums in Grenada in 2016 and 2018, so she remains Queen of Grenada, completely separate to her role as Queen of the UK.

In 1985, Her Majesty returned to open Parliament in St George’s.

There is little appetite among the people to become a republic.

Papua New Guinea (1-10 against)

A former British Protectorate, Papua New Guinea became part of the British Empire in 1888.

The Queen does not get involved in government matters, but plays an important symbolic role.

Unlike other Commonwealth realms she did not become the monarch of Papua New Guinea because its people decided to retain her, they invited her to become their head of state on 15 August 1975.

They wanted a politically neutral head of state who could provide unity and continuity, and the Government wanted to retain all the traditional knighthoods and decorations.

Fiercely loyal, there is no appetite to dump the British monarch as Head of State.

Saint Kitts and Nevis (1-2 against)

St Kitts and Nevis achieved full independence on 19 September 1983 but have an uneasy federation, with some politicians in Nevis claiming the federal government in St Kitts – home to most of the population – had ignored the needs of Nevisians.

A referendum on secession held in Nevis in 1998 failed to gain the two-thirds majority needed to break away.

They have yet to have one on the monarchy.

Saint Lucia (1-3 against)

This island was constantly fought over by the British and the French during the 18th century and has been governed by both.

It obtained independence in March 1967 but since then has had little appetite to dump the Queen.

Saint Vincent and the Grenadines (1-3 against)

In 2009, St. Vincentian voters defeated a proposal for the nation to officially become a republic.

The nation’s prime minister Ralph Gonsalves is a gregarious and exuberant man who described himself to me as an “old fighter against British colonialism”.

Interesting, after Prince Charles and Camilla toured the Caribbean in 2019, he duly announced he was scrapping a vote on the future of the monarchy in St Vincent and the Grenadines.

Solomon Islands (1-5 against)

Once a British protectorate, the Solomon Islands achieved independence as a republic in 1978.

It depends on British and Australian support, so there is little appetite to ditch the British Crown.

Recent visits by William and Kate and Charles have cemented that relationship.

When Kate arrived on the Solomon Islands in 2012 she was immediately crowned with a headdress of fresh flowers.

Tuvalu (1-3 against)

The nine coral atolls that make up the Pacific nation of just 12,000 people launched a consultation on its constitution, which includes considering whether Tuvalu should retain or remove the Queen as the Head of State.

A Parliamentary Select Committee has been set up, and will also look at reviewing whether the nation’s Prime Minister, who currently is decided by party majority, should be directly elected like in the US.

Simon Kofe, Tuvalu’s Minister for Justice, Communication and Foreign Affairs, said a full review was needed to ensure the Constitution “fully meets the needs of the nation in the future”.

The consultation asked the whole of the island’s population ranging from schoolchildren to tribal elders their thoughts on the future before recommendations are made to ministers.

United Kingdom (1-1,000 against)

Whilst polls suggest young people in Britain no longer think the country should keep the monarchy and more now want an elected head of state, it is very unlikely Charles will be ousted as king.

According to a recent survey by YouGov, 41 per cent of those aged 18 to 24 thought there should now be an elected head of state compared to 31 per cent who wanted a king or queen.

That was a reversal of sentiment from two years ago, when 46 per cent preferred the monarchy to 26 per cent who wanted it replaced.

Overall, the survey had better news for the royal family, with 61 per cent favouring the monarchy while just under a quarter thought it should be replaced with an elected figure.

Previous polls have indicated an age divide, with younger generations holding more favourable views of Harry and Meghan than their older counterparts who had overwhelmingly negative feelings about them.