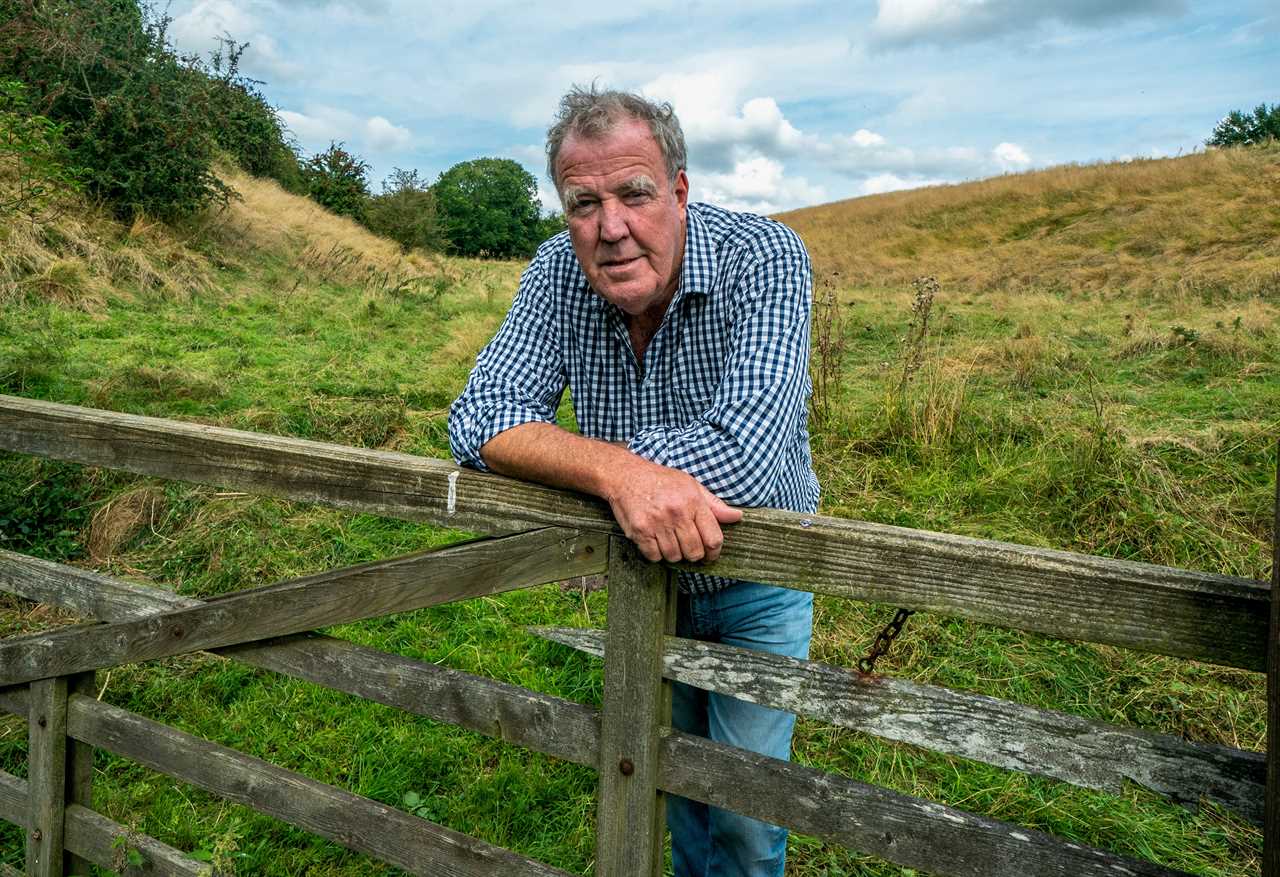

BACK in 2008, I bought a thousand-acre spread in Oxfordshire and employed a local man to do the farmering.

But last year he decided to retire, so I thought I’d take over myself.

Many people were surprised by this, because to be a farmer you need to be a vet, an untangler of red tape, an agronomist, a mechanic, an entrepreneur, a gambler, a weather forecaster, a salesman, a labourer and an accountant.

And I am none of those things.

My bosses at Amazon were so surprised they commissioned an eight-part TV show that would enable viewers to enjoy the “hilarious consequences” of my attempts to manage the woods and the meadows and the fields full of wheat and barley and oilseed rape.

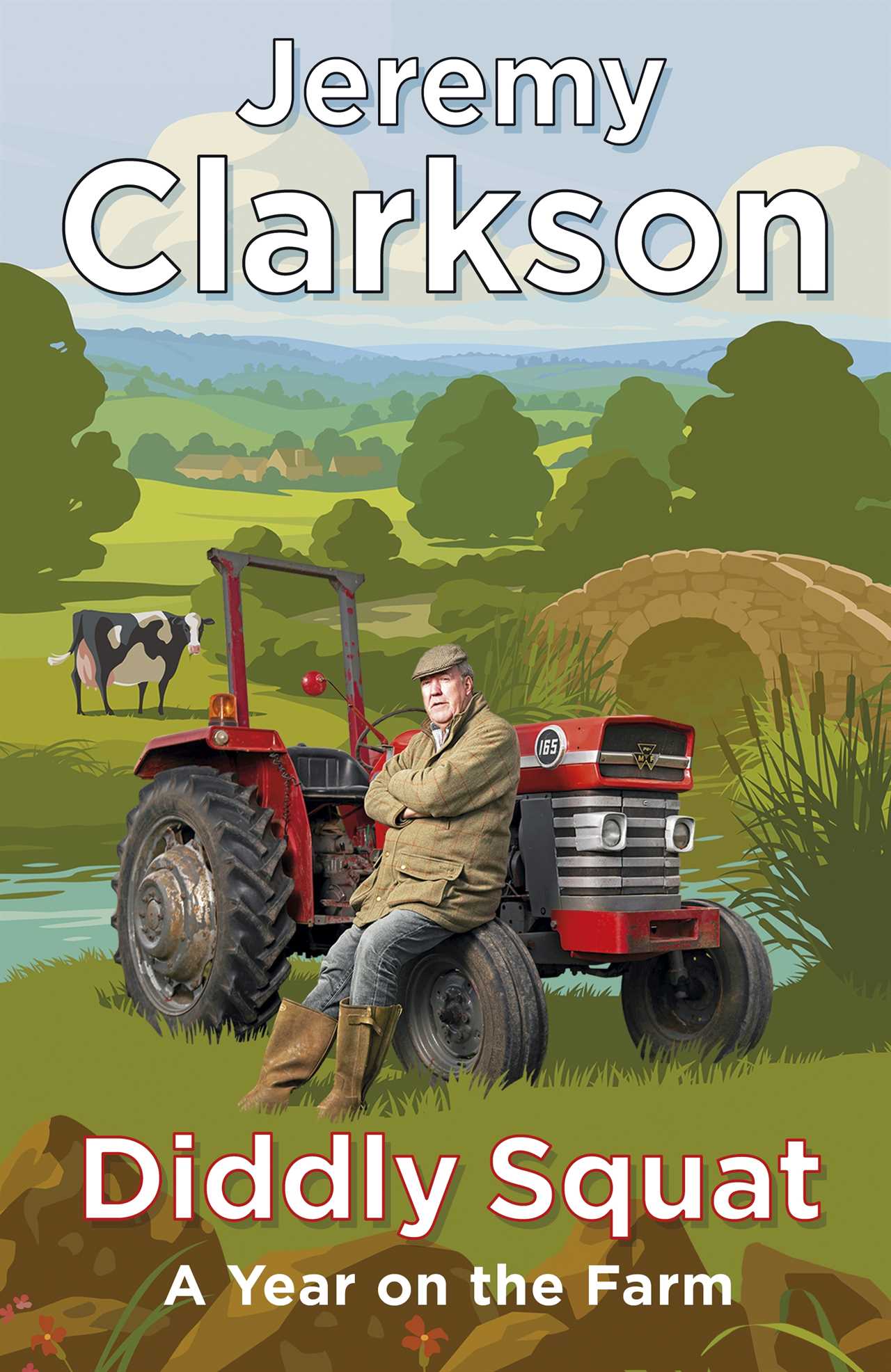

I’d called the farm Diddly Squat because that’s what it makes.

In the past year, I’ve learned that it is completely impossible to attach anything to my tractor and that the weather will always do something you weren’t expecting, and don’t want.

I also learned that whatever you plan on doing with your day on the farm, you will invariably end up doing something else, that sheep are an expensive nuisance, that wasabi isn’t commonly grown in the UK for a reason, and that the Government is endlessly annoying.

Most of all, though, I have learned that it is a great life – and sure as hell beats watching James May organise his tool kit.

Here’s a personal insight into a very different kind of year.

- Diddly Squat: A Year On The Farm, by Jeremy Clarkson, is published on Thursday (Penguin Michael Joseph, £16.99).

SPRING

‘They just want to get on the road so they can be hit by a bus, and burst’

I BOUGHT my sheep at an auction in Thame, Oxfordshire. I had no idea what I was doing. Sheeps were brought into the ring, the auctioneer made machine-gun noises and I went home with 68 North Country Mules.

I’ve no idea what I paid. I couldn’t understand a word anyone said. I then bought two rams, which are basically woolly ball sacks, and in short order, all but three of my new flock were pregnant.

The failures? I ate them, and they punished me for that by giving me heartburn.

Sheeps are vindictive. Even in death.

Sheeps know that human beings are squeamish.

As a result, they never die of something simple, such as a heart attack or a stroke.

No. A sheep’s death has to be revolting. So they put their head in a bit of stock fencing and then saw it off.

Or they decide to rot, from the back end forwards.

Or they get a disease that causes warts to grow in their lambs’ mouths. A sheep’s death has to be worthy of a Bafta.

My sheeps clocked me immediately as a chap who’s eaten too many biscuits, so when I had to move them out of one field into another, they’d do exactly as they were told.

Then they’d wait for me to close the gate and walk home, before jumping over the wall, back into the first field. Did you know they can jump? Well, trust me on this — if a sheep wanted to annoy you, it could win the Grand National.

I bought a drone eventually and programmed the onboard speaker to make dog-barking noises.

This worked well for a day, but then the sheeps just stood there, staring at it. So I had to move them by running about.

And as I trudged home with a bit of lung hanging out of my mouth, they jumped over the wall again. They constantly push for any weakness in the fences. They keep tabs on my routines. And it’s not because they want to get out. They’re in the best field with the best grass.

They just want to get on to the road so they can be hit by a bus, and burst. Their latest game is very irritating. Somehow they’ve worked out how to open the doors on the hen houses.

Even though I have opposable thumbs, I can barely do this — the latches are very stiff. But they can. And at night, they do.

This means the hens can escape, and that means they are killed by nature’s second-most vindictive animal — the fox.

I cannot work out why the sheeps open the doors. It’s not as if they’re after the eggs, or the hens. Which means they must be doing it for sport. They actually enjoy watching the hens being eaten.

And, as an added bonus, it p***es me off, which they enjoy even more.

SUMMER

‘Lisa was thrilled – I know this as she rolled her eyes and slammed the door’

I HAD a wine-powered idea. As people would not be able to buy their vegetables from abroad, or even from Kent, if travel was banned because of Covid, I’d grow some.

Yes. I’d be the broad bean king of Chipping Norton. And the man you call late at night if you need an onion.

My land agent raised an eyebrow and suggested the idea was foolish, as the soil on my farm was so bad.

“Ha,” I responded, full of the confidence you get after 20 years in Notting Hill. I pointed to a nearby field where we had planned to grow spring barley and explained that as spring barley is used to make beer, and all the pubs are shut, there’d be a glut of something no one wants anyway.

“Much better, then, to grow vegetables in it,” I declared triumphantly. Planting the so-called “sets” — or seedlings — was tricky. I bought a machine from the Middle Ages, but that turned out to be useless.

So my girlfriend Lisa and I did it by hand. By which I mean Lisa did it by hand. Lisa was thrilled. I know this because she rolled her eyes, slammed the door and went for a long walk on her own to celebrate.

I, meanwhile, ended up with a 14-acre vegetable patch, and as anyone with a window box knows, all I needed then was a regular supply of rain.

But I can’t remember when it last rained here.

The ground is parched, cracked. I’m living in a dust bowl.

Last night, having marinated myself in more wine, I was looking into the possibility of using a hovercraft as a water dispenser.

That’s had to be shelved this morning, however, as the amount I’ve spent on my vegetable operation already means each broad bean will have to be sold for £17.

There’s only one solution as far as I can tell. I’m going to have to call Donald Sutherland and Kate Bush, and get the plans to that rain-making machine they made.

AUTUMN

‘I’m tempted to fit it with flamethrowers modelled on the guns in Aliens’

I HAVE just seen footage of a flamethrower being towed behind a tractor and I immediately wanted one, because who wouldn’t want a flamethrower attachment?

I’d have one on my ironing board if I could.

But this one looked as if it had been made out of scaffolding poles and cow bells. This is an issue that runs throughout farming.

There’s been a small amount of effort made in recent years to give tractors a bit of snazziness, but everything else is designed to do a job and be put on sale.

Part of the problem, I suspect, is that a lot of farming equipment has been designed by farmers themselves.

And you only have to look at a farmer’s three-piece suite to know that aesthetics rarely feature in his list of “important things”.

The farmer wears overalls that make him look fat.

He cuts his hair by dipping it annually into his combine harvester, and he continues to wear an oily tie that he found 15 years ago, holding the leaf springs on his trailer together.

There is, however, an exception to all this: The JCB telehandler — a machine with a telescopic arm that can lift and move heavy loads. I managed to go for 59 years without one in my life, and now I have no idea how.

Yesterday I used it to transport crates of empty bottles to my new water-bottling plant and even though it’s me we’re talking about, and I’m neither practical nor careful, I didn’t drop one.

This evening, after I’ve used it to shovel the wheat into a neat pile, load some barley on to a truck and fetch some logs, I shall go to the pub in it, then tomorrow I will put a pallet on the forks and raise a child high into the apple trees to collect the hard-to-reach fruit.

Apparently you’re not supposed to use it for this purpose, but I can’t see why.

And here’s the best bit.

Unlike anything else in the farmer’s barn, it’s as cool as the kit they used on Thunderbirds.

It is the best of both worlds, then — something you want and something you need.

And now, because I’m not a proper farmer yet, I’m tempted to fit it with flame-throwers modelled on the guns in Aliens, and maybe some lasers.

WINTER

‘At a rough guess, I’d say 20% of my trees have chainsaws stuck in them’

IT’S been an exciting morning on the farm. I’ve swapped 60 tons of hardcore lying around in the yard for 90 tons of topsoil.

Although when I say “I’ve” swapped it, what I actually mean is that “I’ve” been sitting at the kitchen table while a man in overalls has swapped it.

I was going to help — but it was one of those damp north-easterly mornings that can penetrate all known materials, including skin and bone.

So I went back inside, took off my coat and my hat and my wellies and made some toast.

There is, however, no getting round one job.

No matter what the weather’s doing, I have to fire up my six-wheel-drive ex-Army Supacat, attach the ex-Army trailer using an extremely manly Nato hitch and head into the woods for firewood.

Firewood used to be a simple thing, but now the Government has decided to complicate matters by banning the sale of wet logs so people don’t burn them.

Quite why anyone would want to try to burn a wet log, I have no idea. It’d be like trying to stay warm by burning a wet towel or a wet dog.

But, anyway, as I understand it, I can no longer use soggy, mossy logs that have been lying on the ground, and instead — for the sake of the environment — it seems I have to chop down trees.

Naturally I’m not very good at it. In my head, a chainsaw is a tool of the gods.

Brandish one and you’re the most powerful person in the room, unless someone has an AK47 — and even then it’s by no means a foregone conclusion.

And yet, when I have one in my hands, I always have the sense that I’m the one most likely to be injured.

I am in constant fear, for example, that the chain will come off and cut me in half. Or I will slip, and then I’ll be in A&E with all the other farmers, having a limb sewn back on.

If I take a brave pill and get cracking, I will only ever get halfway into the tree trunk before it jams, and I’m not able to unjam it, because all the safety equipment I’m wearing means I can’t see anything.

At a rough guess I’d say 20 per cent of the trees in my woods have chainsaws stuck in them.

WET AND ILLEGAL

Sometimes though, I will get a tree to fall over, and then, after I’ve climbed out of the branches and repaired my lacerated face, I have the job of loading it into my trailer and trying to get it out of the woods. I can’t do that either.

Thanks to their ability to lock all the wheels on either side, just as a tank can lock its tracks, Supacats can turn in their own length, which makes them incredibly manoeuvrable.

But when a trailer is attached, the turning circle is measurable in light years.

This means I have to cut down more trees to create a path back to the world, and because there’s no more space in the trailer, they have to lie on the ground, becoming wet and illegal.

And do you know how long a tree lasts in my firepit?

Well, if it’s a good size I’d say: “Less than an hour.”

And then it’s back to the wood for more deforestation and devastation.

If only we could still use coal. But we can’t.

And when the day comes when we aren’t allowed to use oil and gas either, the only way we will be able to stay warm is to go for a brisk walk.

I did that the other day, and in a field I thought I’d planted with grass I found thousands and thousands of radishes. Which on reflection may be adolescent turnips.

Like I said, I may not be cut out for farming, because either I don’t know what I’m doing or I can’t be bothered to do it.